The first primary of the 2018 midterm elections, in Texas, is barely eight weeks away. It’s time to ask: Will the Russian government deploy “active measures” of the kind it used in 2016? Is it possible that a wave of disinformation on Facebook and Twitter could nudge the results of a tight congressional race in, say, Virginia or Nevada? Will hackers infiltrate low-budget campaigns in Pennsylvania and Nebraska, and leak their e-mails to the public? Will the news media and voters take the bait?

By most accounts, the answer is likely to be yes—and, for several reasons, the election may prove to be as vulnerable, or more so, than the 2016 race that brought Donald Trump to the White House.

Part of the explanation is political: the 2018 midterms are shaping up to be extraordinarily competitive. Consider the spectacle currently unfolding in Virginia. Before the most recent election, on November 7th, Republicans controlled Virginia’s House of Delegates by a comfortable sixteen-seat majority. In a wave of Democratic wins, propelled by the state’s highest turnout in twenty years, the Republican majority nearly evaporated. Final control of the House now rests on the results of the 94th District, which is deadlocked at 11,608 votes apiece. The Virginia Board of Elections planned to draw the name of a winner out of a pitcher, a tactic unused in Virginia in more than four decades, but, on December 26th, the state postponed the plan, because of pending court challenges. If the Republican incumbent David Yancey loses to the Democrat Shelly Simonds, the House will be tied fifty-fifty, and the two parties will share power.

Nationwide, voters will have similar motivations to turn out in 2018, an election with higher stakes than any midterm in memory. Voters could determine control of both chambers of Congress, and, indirectly, the fate of President Trump. If Democrats take control of the House, they are likely to face pressure to embark on an impeachment. Party leaders still say that discussion is premature—and, perhaps, counterproductive, if talk of impeachment inspires Republican voters to come out in defense of Trump. In polls, however, three out of four Democrats already favor impeaching Trump. In December, fifty-eight House Democrats—nearly a third of their caucus—voted to start debate on impeachment.

For Democrats to win control of the House, they will need to gain twenty-four seats. Historically, a President’s party loses twenty-five seats in a midterm, which would give the Democrats control by one vote. When I reported, in May, on the outlook for 2018, the chances of a Democratic victory looked small, because gerrymandered districts have reduced the number of competitive elections, and morale among Democrats was low. Seven months later, the chances of Democrats taking the House are still modest, but less so: The President remains uniquely unpopular, and Democratic surges, like those in Virginia and Alabama, have produced results that were once thought impossible. By the end of the year, political analysts figured that as many as forty races will be competitive in 2018, and Republicans hold thirty-two of the seats in question. That is the makings of a brutally tight year—and a perfect setting for hackers to make mischief.

“An attacker who wants to affect the national outcome could try targeting all of those races, find the states where the election systems are most weakly protected, and strike there,” J. Alex Halderman, the director of the Center for Computer Security and Society at the University of Michigan, told me. In the language of hacking and cyber-defense, the 2018 midterms present an unusually large “attack surface,” because of the sheer number of competitive races. “About a dozen states still rely on obsolete paperless voting machines, and most states fail to routinely conduct rigorous post-election audits,” he said.

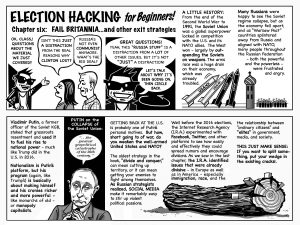

On a technical level, the American election system is almost as vulnerable as it was in 2016. According to U.S. intelligence, Russian hackers tested the vulnerabilities of registration rolls in twenty-one states, but did not alter the vote tallies. Halderman, who testified recently in Congress about gaps in election defenses, told me, “Unfortunately, there haven’t been widespread security improvements so far. We can be sure that our adversaries have been paying attention, and so they may be more likely to try attacking election systems in November.” At the Def Con hackers’ conference in July, attendees demonstrated that they could break into thirty voting machines of multiple types, some in as little as ninety minutes. Without altering the results, hackers could sow doubt about the outcome by shutting down or disrupting voting machines on Election Day.

In October, Senator Richard M. Burr, a Republican of North Carolina, who is chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, warned political candidatesthat they should expect Russian interference in 2017 and 2018. “The Russian intelligence service is determined—clever—and I recommend that every campaign and every election official take this very seriously.” The committee’s ranking Democrat, Mark Warner, of Virginia, added a specific warning about the vulnerabilities across multiple states. “You could pick two or three states in two or three jurisdictions and alter an election,” he said.

Two weeks later, Attorney General Jeff Sessions testified before Burr’s committee, and Ben Sasse, a Republican of Nebraska, asked if the U.S. is ready to fend off further Russian interference. Sessions replied, “Probably not, we’re not.” Despite voluminous reports by U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies, Sessions asserted that the Justice Department remains incapable of addressing the challenge. He said, “The matter is so complex that for most of us we’re not able to fully grasp the technical dangers that are out there.”

Since 2016, Russia has not withdrawn its interference in American politics; it has expanded it. In the Washington Post this week, Adam Entous, Ellen Nakashima, and Greg Jaffe described the ways in which Russian trolls have ventured beyond Twitter bots and Facebook posts to write full-fledged articles for opinion sites, such as CounterPunch, which don’t have the resources or structure to vet whether “Alice Donovan,” a self-described freelancer with a distinctly pro-Russian angle, is a real person.

Nearly four years after U.S. officials intercepted a classified cable from Russia’s military intelligence unit, laying out a playbook for the use of fake online personas to spread disinformation abroad, the U.S. has yet to mount a full-scale response. According to the Post, U.S. spy agencies have planned a “half-dozen specific operations to counter the Russian threat,” but “one year after those instructions were given, the Trump White House remains divided over whether to act.”

After a year in office, Trump and his aides continue to resist adopting greater protections against Russian interference, because Trump is insulted by the intelligence community’s finding that Russia aided in his victory. (“The president is right. The Democrats are using the report to delegitimize the presidency,” a White House official told the Post.) If any action is taken, it will likely come from Congress, where several bills seek to impose federal standards for voting machines, and provide funding to states to overhaul outdated equipment and install software patches. It might be too late: By this point in the 2016 election cycle, Russian hackers had already broken into the Democratic National Committee, and had been rooting around in the e-mail system for four months.

How much of an effect could Russian interference actually have in 2018? The effects could be meaningful, even if they never touch the tallies directly. “More and more Americans seem to distrust the basic institutions of democracy. Unfortunately, that means that an attacker could do serious damage by throwing election results into further doubt,” Halderman said. “Sabotaging election infrastructure to make it fail on election day, resulting in long lines and other visible chaos, would be even easier than actually stealing votes.”

Source: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-the-2018-midterms-are-so-vulnerable-to-hackers