The race for control of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court could change the course of the entire country.

Last month, Mary Lynne Donohue drove me along Superior Avenue, a long artery that runs across Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a small industrial city on Lake Michigan. We headed west from the lake, passing expansive, stately homes that grew more modest the farther we got from the water. “You can see it’s exactly the same on both sides,” Donohue said, gesturing at the houses lining the street. In 2011, Republicans redrew the state’s district maps, using Superior Avenue to cleave the Twenty-sixth Assembly District, which for decades had encompassed the entire city—and had been reliably Democratic. The new map kept homes to the south of Superior in the Twenty-sixth, but put those to the north into the Twenty-seventh, which used to comprise the rural, Republican areas around Sheboygan. In every subsequent election, Republicans have won both the Twenty-sixth and the Twenty-seventh.

About halfway through town, Donohue, a retired attorney who is the president of Sheboygan’s school board, abruptly turned the car north, up a small side street, and slowed down in front of a brown, ranch-style house. In 2011, the house belonged to Mike Endsley, a Republican who, the previous year, had won the Twenty-sixth in an upset. The boundary line drawn by the Republicans had jagged up from Superior to keep Endsley’s house in the district.

Donohue parked, stood in front of the house, and shook her head. “In the high philosophy of redistricting, one of the basic goals is to keep communities together,” she said. Endsley retired almost a decade ago; now the two Assembly members and the state senator who represent the city all live in conservative hamlets outside it. Donohue went on, “When you cut municipalities in half, that municipality no longer has its own voice. It’s been taken away.”

The 2011 maps had been drawn in secret, in a locked wing of a law firm across the street from the Wisconsin state capitol. The year before, Republicans had captured all branches of the state’s government—a sweep carried out as part of redmap, a project promoted by Karl Rove to secure G.O.P. control of redistricting in swing states. After mapping dozens of possible scenarios, Republican legislative leaders settled on the most extreme partisan gerrymandering possible. Since then, they have never won fewer than sixty of the state’s ninety-nine Assembly seats, even when Democrats have won as much as fifty-three per cent of the aggregate statewide vote.

Donohue, who is seventy-three years old and has curly chestnut hair, grew up in Sheboygan. She has been a community-minded activist since high school, when she won the Young American Medal for Service, which L.B.J. put around her neck in a ceremony in Washington, D.C. After college, she and a friend took a ten-month trip across the country in a 1960 Volkswagen bus that they called the “flying tomato,” and then she applied to an auto-mechanics program at a technical college and to the University of Wisconsin Law School. She was rejected by the technical college but got accepted to law school. She eventually returned to Sheboygan to work on cases involving domestic-violence victims, tenant disputes, and disability benefits, among other things.

In 2015, Donohue and eleven other plaintiffs sued the state, alleging that the 2011 gerrymandering violated their constitutional rights. The plaintiffs won in federal court, scoring the first victory against partisan redistricting in three decades—until, on appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the case for lack of standing. (The Justices argued that plaintiffs were needed from each of Wisconsin’s ninety-nine Assembly districts.) “I started to cry,” Donohue said. “You felt a sense of hopelessness.” Nonetheless, in 2020, Donohue ran for the Twenty-sixth Assembly District seat. “I couldn’t leave it uncontested,” she told me. “It’s like not showing up on the battlefield.” She lost by eighteen points.

In 2021, the Republican-controlled state legislature and Tony Evers, Wisconsin’s Democratic governor, each proposed new maps, which are required by law every ten years. The Governor’s maps were based on models from a nonpartisan redistricting agency that he created. The Republicans reused the 2011 maps, with adjustments that minimized Democratic gains. A legal battle ensued, and, in November of that year, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 4–3 conservative majority ruled, in a decision it described as “apolitical,” that the new maps should make the “least change” possible to the 2011 maps. In a dissent, Justice Rebecca Dallet called the ruling a “striking blow” to representative democracy in Wisconsin. The least-change approach, she wrote, “perpetuates the partisan agenda of politicians no longer in power.” Dallet noted that the least-change standard has no basis in the U.S. or Wisconsin constitutions. “I believe in the separation of powers,” Dallet told me, in her office in the state capitol. “In order for that to function, you have to be able to have people’s votes count; ‘one person, one vote’ has to mean something.”

Evers went on to draw new maps based on the least-change standard, but added a seventh, majority-Black Assembly district in Milwaukee to reflect the growth in the city’s Black population. Evers cited the need to satisfy Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits denying citizens equal access to the political process on the basis of race. The Wisconsin Supreme Court approved, with Justice Brian Hagedorn, a conservative, breaking from his colleagues to join the liberals. Republicans made an emergency appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that Evers’s new maps, which modestly diminished their advantage, amounted to a “21st century racial gerrymander.” The Court intervened through its so-called shadow docket—which is used to issue unsigned opinions without hearings or briefings—to reject Evers’s maps and rebuke Hagedorn’s opinion. (This has widely been interpreted as a signal that the Court is prepared to gut Section 2, the last remaining effective part of the Voting Rights Act.) The case was sent back to Wisconsin, where Hagedorn reversed himself and endorsed the original maps proposed by the Republicans, entrenching their control, in theory, in perpetuity. In the next election, Republicans won a veto-proof supermajority in the State Senate and came within two seats of one in the Assembly.

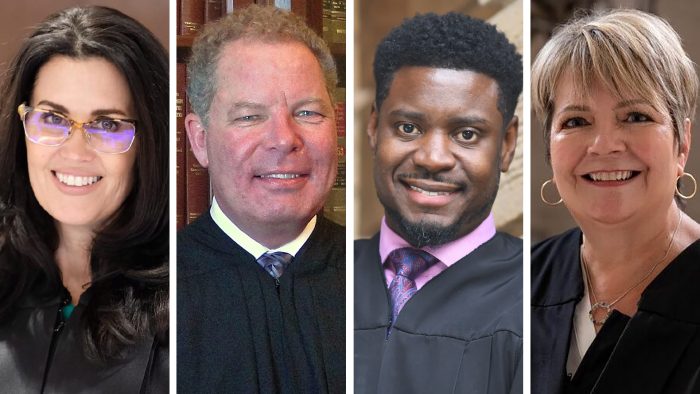

On April 4th, Wisconsin will hold an election to replace Justice Patience Roggensack, a retiring conservative, which could upend the Court’s ideological balance. Janet Protasiewicz, a circuit judge in Milwaukee, will face Daniel Kelly, a former state Supreme Court justice who was appointed by the former Republican governor Scott Walker, in 2016, to fill a vacancy. (In 2020, Kelly lost a bid for reëlection.) Already the most expensive judicial campaign in American history, the race is expected to cost more than forty million dollars, most of it spent by outside groups. (When Roggensack was elected, twenty years ago, outside spending totalled twenty-seven thousand dollars.) The outcome could reshape an institution that has helped transform Wisconsin into what the journalist David Daley calls a “democracy desert”—a place where voters stand little chance of effecting political change. In its most recent biannual report, the Electoral Integrity Project, which measures the democratic attributes of electoral systems, gave Wisconsin’s district maps twenty-three points out of a hundred, the worst rating of any state in the country. The score is on par with that of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The media tends to focus on the federal judiciary, and particularly the U.S. Supreme Court, but state courts handle more than ninety per cent of cases in the American judicial system. “The whole country was distracted, in some ways, by the successes of the Warren Court in the sixties,” Jeff Mandell, a co-founder of Law Forward, a nonprofit progressive law firm in Madison, told me. “You had organizations like the A.C.L.U. and others that were built up largely around going to federal court for relief. At some point, the right recognized that state courts can be much more powerful. Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction; they only hear certain kinds of cases. State courts can hear and decide anything. They also get a lot less attention, so they can radically change what’s happening in a state or region of the country.”

The U.S. is one of the only countries in the world to hold judicial elections, and these elections are increasingly dominated by dark-money groups. In 2014, the Republican State Leadership Committee launched a project called the Judicial Fairness Initiative, which focussed exclusively on winning state judicial elections. Last year, it backed winning conservative candidates for three Supreme Court seats in Ohio and one in North Carolina, flipping control of that Court in a change with enormous implications for abortion access and gerrymandering.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court has played a central role in an ongoing effort to overturn the state’s democratic norms. In 2015, the Court let stand one of the most restrictive voter-I.D. laws in the country. As a result, Wisconsin, which was once among the states where it was easiest to vote, is now ranked forty-seventh by the nonpartisan Cost of Voting Index. In a Facebook post, Todd Allbaugh, an aide to a Republican state senator, described a caucus meeting in which several Republican legislators were “giddy” over the voter-I.D. bill’s potential to suppress the votes of college students and minorities. Allbaugh quit the Party in protest.

That same year, the Court abruptly ended a criminal investigation regarding alleged coördination between Republicans and dark-money groups. It also issued an unprecedented order for prosecutors to destroy all the evidence that they had gathered. (A partial set of documents, leaked to the Guardian, revealed apparent quid-pro-quo payments, including seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars paid by the owner of a company that had manufactured lead paint to a conservative dark-money group in exchange for legislation granting legal immunity from lead-poisoning claims.) The conservative justices David Prosser and Michael Gableman refused to recuse themselves in the case, even though the groups being investigated had spent millions of dollars on their campaigns.

Since 2018, when Evers defeated Walker for the governorship, the Court has also played a decisive role in battles over the separation of powers. During the 2018 lame-duck session, the legislature stripped the governorship and the attorney general’s office (which had also been won by a Democrat) of significant powers. The legislature also effectively created its own attorney general’s office by giving itself the power to hire a special counsel, which it has used to file a bevy of lawsuits against Evers and other officials. In 2020, the Wisconsin Supreme Court overruled two lower-court opinions that said the lame-duck changes were unconstitutional.

More recently, the Court ruled that Fred Prehn, a Walker appointee to the board of the Department of Natural Resources, could stay on after his term expired, in May, 2021, until his replacement was confirmed—even though the legislature had refused to hold hearings on Evers’s nominee for the opening. Prehn’s extended tenure insured that the board remained under a 4–3 conservative majority. Text messages uncovered in an open-records request showed that Prehn coördinated the extension with Walker, industry lobbyists, and Republican legislators. “Senators are asking me to stay put because there [sic] not gonna confirm anyone,” Prehn wrote to a former D.N.R. warden. “So I might stick around for a while. See what shakes out. I’ll be like a turd in water up there.” During this time, Prehn cast the deciding vote to block groundwater standards for pfas, also known as forever chemicals, which have been linked to cancer, liver damage, decreased fertility, and increased risk of asthma and thyroid disease.

Following the 2020 Presidential election, Wisconsin was the only state in the country whose Supreme Court held a hearing on election challenges filed by Donald Trump. Joe Biden had won the state by nearly twenty-one thousand votes; Trump’s lawyer, Jim Troupis, asked for the results from the state’s two most populous and most Democratic counties to be thrown out, mainly because ballots had been cast using drop boxes. Though drop boxes had been used in counties across the state, and they had not been subject to legal challenge prior to the election, the Court seriously entertained the argument, ultimately ruling 4–3 to let the results stand. (Hagedorn again broke with his fellow-conservatives, but on procedural grounds—he wrote that the case had been brought too late.) Two years later, the Court outlawed drop boxes. In that case, Rebecca Bradley, writing for the majority, compared Wisconsin’s 2020 contest to elections conducted by Bashar al-Assad, Kim Jong Il, and other despots. “Throughout history, tyrants have claimed electoral victory via elections conducted in violation of governing law,” she wrote. “For example, Saddam Hussein was reportedly elected in 2002 by a unanimous vote of all eligible voters in Iraq.”

In the wake of the Dobbs decision, the outcome of the Wisconsin Supreme Court race is nearly certain to decide the future of abortion access in the state, which is currently being governed by an 1849 law that criminalizes abortion except to save the life of the mother. Under this law, physicians who perform an abortion can be imprisoned for up to six years and stripped of their medical licenses. Protasiewicz, the first judicial candidate in the country to be endorsed by emily’s List, is outspoken about her pro-choice views. Kelly has been endorsed by the state’s major anti-abortion groups and is pro-life.

Last month, Walker, the former governor, told National Review that “everything” is on the line in this election. “This is their chance to undo everything that we’ve done over the past dozen years,” he said. Wisconsin is arguably the country’s most pivotal swing state, so the election has national implications, too. “The United States has this unique-in-the-world system where an individual state can tip the Presidential election, because of the Electoral College,” Ben Wikler, the chairman of the Wisconsin Democratic Party, said. “For better or worse, Wisconsin seems permanently poised right on the fulcrum. That means that tiny shifts and laws in this one small Midwestern state can ripple out to affect the whole future of American democracy.”

Last month, a few dozen citizens crammed into a small community room in the Black River Falls library for a lunchtime meet and greet with Protasiewicz. Volunteers brought homemade chili and corn bread. Protasiewicz schmoozed energetically with the crowd, which was largely older and white, with a smattering of attendees from the Ho-Chunk Nation, including its President, Marlon WhiteEagle. Dressed in a white leopard-print jacket, Protasiewicz highlighted the most prominent issues of her campaign: gerrymandering (she was unapologetic about having called the maps “rigged”), abortion (“Can you imagine what medical science was like in 1849?”), and the Court’s role in the 2024 Presidential election (“By one vote, our 2020 election in the state of Wisconsin managed to stand”).

Protasiewicz grew up in a Polish family on the south side of Milwaukee. Her mother taught at a Catholic school and her stepfather at a public one. Her stepfather was in a union and made much more money than her mother did. The contrast gave Protasiewicz an abiding appreciation for the labor movement. “I started to learn about the value of being represented by a union, what they do to give you—quite frankly—a living wage,” she told me. She went to Marquette University for law school, supporting herself with odd jobs—running the Milwaukee office of the League of Women Voters, writing concert reviews for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. (“Although Seals did not move with energy,” she wrote of Son Seals, a blues guitarist, “an undercurrent of vitality was evident.”) After law school, she spent twenty-five years at the Milwaukee County D.A.’s office, where she worked on a variety of cases, including domestic abuse, armed robbery, and the termination of parental rights.

In 2011, the state’s Supreme Court, overruling a lower court’s order, upheld Act 10, Walker’s signature anti-labor law, which all but eliminated collective-bargaining rights for public employees in Wisconsin. (The bitter deliberations included accusations that David Prosser, one of the Court’s conservative justices, entered the chambers of his liberal colleague, Ann Walsh Bradley, and put her in a choke hold; Prosser denied choking her, though he testified that he could feel the “warmth” of Bradley’s neck in his hands.) Protasiewicz participated in protests against Act 10, which also slashed the state’s contribution to workers’ health care and pensions, resulting in an average take-home pay cut of nearly nine per cent. “I was single then, and scraping to get by,” Protasiewicz, who was a member of a public-employee union for state prosecutors, told me. (Her support for labor has helped secure endorsements from many of the major unions in the state.)

Democrats have won fourteen of the past seventeen statewide elections in Wisconsin, and that success may have something to do with voters like Irv Caldwell, who was listening intently at the Black River Falls meet and greet. Caldwell, a seventy-four-year-old retired truck driver, has voted for both Democrats and Republicans. For the past decade, he’s felt that the state Republican Party has pitted Wisconsin’s electorate against itself. “Walker has really done a number on us,” he said. “It never used to be such a divide.” He is particularly concerned about gerrymandering. “You could straighten out a whole lot of things without that,” he said, noting that Black River Falls had a Democratic state senator until the town was moved into a different district last year. He’s also worried about abortion and L.G.B.T.Q. rights, because he has two daughters, the younger of whom is gay. “I see so much of her girlfriend—I know a lot of their friends—and we’re like family,” Caldwell said. (Kelly, a long-standing critic of same-sex marriage, wrote, in 2014, that it “will eventually rob the institution of marriage of any discernible meaning.”)

Caldwell added that he wasn’t planning to get involved in the election, “besides shooting my mouth off.” On his way out, though, I saw him grab a Protasiewicz yard sign.

Green Bay, a working-class city with a large Catholic population, has long been a flash point in the battle over abortion. Days before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an ob-gyn who lives in Green Bay, had already stopped performing abortions. “There’s a law in Wisconsin that, even with a medication abortion, there’s a twenty-four-hour waiting period between your first visit and getting the medication,” she said. “Knowing that people were travelling hours just to get there, we didn’t want them to be stuck.” The morning that Dobbs came down, Lyerly burst into tears. “We knew it was going to happen, but when it did it felt like half of you just disappeared,” she told me.

Lyerly, who has long brown hair and a disarming smile, was born and raised near Charlesburg, a hamlet south of Green Bay that was named after her great-great-grandfather. (It was “a supper club and a church, pretty much,” she said.) She was the first in her family to go to college. Afterward, she bounced around, working at an abortion clinic in Atlanta, a doctor’s office on an Alaskan island, and a rural hospital in north Georgia, where she did intake for impoverished patients. “Seeing people who were coming out of the mountains, who didn’t have running water and were suffering from uncontrolled diabetes—that fuelled me and continues to fuel me,” she said. She decided to apply to medical school and was accepted at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where, as a thirty-two-year-old mother, she was the oldest student in her class.

In 2012, an anti-abortion activist firebombed a Planned Parenthood clinic outside Appleton. The following year, the only abortion clinic in Green Bay shut down. By the time that the Dobbs ruling was issued, there were just four abortion clinics left in the state: two in Milwaukee, one in Madison, and one in Sheboygan, where Lyerly had been commuting twice a week. Now she’s stopped working in Wisconsin altogether. “I can’t look my patients in the eyes and say, ‘I know exactly what to do for you, but I can’t, because the state won’t let me,’ ” she said. (She currently practices out of two hospitals in rural Minnesota.)

Lyerly is one of three doctors who joined a lawsuit brought by Josh Kaul, Wisconsin’s attorney general, challenging the state’s 1849 abortion law, which was written before germs were known to cause disease. (The lawsuit claims that subsequent laws regulating abortion supersede the earlier ban.) Governor Evers, who, the day after Dobbs, said that women in Wisconsin have become “second-class citizens,” called two special sessions of the legislature to address the 1849 law—first to repeal it, then to authorize a voter referendum—but both times the legislature gavelled in and immediately gavelled out. He has offered clemency to doctors who perform abortions, but, because the law has a six-year statute of limitations, they could be prosecuted after he leaves office. No other state is operating under a more extreme abortion ban.

“Dobbs has affected physicians’ judgment of these situations,” Abigail Cutler, an ob-gyn based at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals, in Madison, said. “They’re thinking twice.” Cutler is concerned that the law could hurt the ob-gyn residency at the University of Wisconsin’s medical school. “Abortion is not something that just lives out in the satellite over here,” she said. “It is deeply integrated into ob-gyn care. Miscarriage management, fertility management, contraception—abortion can be a part of each.” Post-Dobbs, Cutler has performed life-saving abortions, but operating within that narrow legal exception is fraught with fear. She noted that pregnancy exacerbates conditions like cervical cancer and chronic kidney disease: “How close does someone have to be to that line of death in order for it to be considered saving their life?”

Three years ago, Lyerly ran for the State Assembly. She focussed her campaign on covid. “I stayed as far away from abortion as I could,” she said. “It was just too hot. But now I talk about it all the time, because we have to.” (She lost the election.) This month, she starred in a couple of ads for A Better Wisconsin Together, a liberal group supporting Protasiewicz. In one, Lyerly warned of the 1849 law’s potential impact on a state already starved for physicians. “It’s all at stake with the Supreme Court election,” she said. As a regional official for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, she has been trying to help fellow ob-gyns navigate wrenching decisions in which they have to balance their ethical obligation to help patients with the prospect of breaking the law. “Just the other day, a colleague of mine called me and said she had a patient who was seven weeks pregnant,” Lyerly told me. “The patient ordered pills for a medical abortion. She’s afraid if she takes them, she could go to jail. She doesn’t know what to do. I told my colleague the criminal abortion ban does not affect her, so she should not worry. My colleague said, ‘O.K., I’ll tell her that.’ Then there was a long pause and she asked, ‘What about me? Am I in danger?’ ”

On Valentine’s Day, the Northeast Wisconsin Patriots, a conservative group founded in the Tea Party era, hosted a forum for Daniel Kelly and his rival on the right, a circuit judge named Jennifer Dorow. (The primary was a week away.) The meeting was in the Lawrence town hall, near Green Bay, and volunteers brought heart-shaped cookies. Toward the back, a table almost overflowed with copies of The New American, the magazine of the John Birch Society. Buttons with a picture of the Constitution, overlaid with the words “as written,” were for sale. A man in front of me looked around the room at the hundred or so attendees and whispered to his companion, “There’s not enough of us.”

During the forum, someone asked Kelly about fund-raising. Kelly, who so far has raised a fourth as much as Protasiewicz, indicated that he was confident he’d be bringing in outside money. “I read the newspapers along with everybody else,” he said, smiling coyly. “I don’t have any conversations with independent expenditure groups, but I’ve been reading stories that say that they’re going to bring in enough money to the state of Wisconsin to insure that I can be competitive.”

Kelly seemed to be alluding to groups funded largely by Richard Uihlein, a billionaire shipping magnate from Illinois, whose judicial-focussed pac, Fair Courts America, spent three million dollars to boost Kelly in the primary and has spent nearly five million so far in the general election. (Uihlein spent upward of six million dollars to help U.S. Senator Ron Johnson win in Wisconsin last November. A Democratic politician recently told me, “Dick Uihlein is the Wisconsin Republican Party now.”) Kelly, who prides himself on his pugnaciousness, ran a caustic campaign against Dorow, refusing to endorse her if she won the primary and questioning her competence and ideological reliability. The scorched-earth tactics worked: he beat her narrowly to make the April runoff.

Since then, Protasiewicz has outspent Kelly by nine million dollars on television ads alone. Her success is a reflection of the state’s Democratic Party and liberal dark-money groups largely catching up to the right in fund-raising. (In the primary, one such group, A Better Wisconsin Together, had spent more than two million dollars attacking Dorow, who was widely perceived as the stronger general-election candidate, as soft on crime.) This troubles some progressives, who see Wisconsin’s tradition of clean, transparent elections slipping away for good. “We’re just under an avalanche of big money,” Matt Rothschild, the executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a nonpartisan organization that tracks money in politics, said. He noted that, in 2015, Republicans gutted the state’s campaign-finance laws, allowing individuals to donate as much as twenty thousand dollars directly to a Supreme Court candidate—six times more than what the federal government allows for donations to a Presidential candidate. “It is a tragedy for democracy, for public participation, and for equal voice in our politics,” he said. “And it cuts at the core of self-rule and self-government when you have so much money coming from outside the state, from billionaires on the left and billionaires on the right. Why should they tell us who should be our Supreme Court justice?”

Daniel Kelly grew up outside Denver and moved to Wisconsin after high school, to attend a small Christian college. In 1988, he enrolled in the Christian Broadcasting Network’s law school, which was founded by the televangelist Pat Robertson and later renamed Regent University School of Law. Robertson’s goal, according to his authorized biographer, was for his graduates to “gradually infiltrate secular society.” (The school was unaccredited when Kelly enrolled, but had received provisional accreditation by the time he graduated.) During his last year there, Kelly edited the inaugural issue of the Regent University Law Review. “We believe that God’s law has something to say about every area of law,” he wrote, in its opening essay. “Today it is popular to argue that law is nothing but a humanly created instrument. . . . Law originates with God and is impressed on His creation, including mankind.”

After graduating, Kelly completed a clerkship in Washington, D.C., and eventually moved back to Wisconsin. He became a commercial litigator representing manufacturers, developers, financial institutions, and technology companies. Following the 2010 Republican sweep of Wisconsin’s state government, he began taking on more political clients. He was hired to defend the state’s Republican Party in a lawsuit over the 2011 redistricting maps. He has also given legal advice to Wisconsin Right to Life, one of the pro-life organizations endorsing him. Another of these groups, Pro-Life Wisconsin, not only opposes abortion but also favors banning contraception, which, according to its Web site, “facilitates the kind of relationships and even the kind of attitudes and moral character that are likely to lead to abortion.”

In 2016, Walker picked Kelly to finish the term of a retiring justice. In his application for the appointment, Kelly, who had no judicial experience, included an article he had written that likened affirmative action to slavery. “Morally, and as a matter of law, they are the same,” he wrote. In a 2013 blog post, which he deleted prior to the appointment, he had also compared social-welfare programs to slavery. “We all see involuntary servitude every day,” he wrote. “When the recipients are people who have chosen to retire without sufficient assets to support themselves, we call the transfer Social Security and Medicare.”

On the Court, Kelly’s first majority opinion barred the city of Madison from prohibiting loaded guns on public buses. In 2020, he ran his reëlection effort out of the headquarters of the state Republican Party, which also donated roughly three hundred thousand dollars to his campaign. (A day after a gunman killed five people in Milwaukee, Kelly held a fund-raiser at a shooting range.) He lost and was subsequently hired by the state G.O.P. to work on “election integrity issues.” Andrew Hitt, who, in 2020, was one of ten Party officials who tried to become illegitimate electors for Trump, testified to the January 6th congressional committee that he had “extensive conversations” on “election law matters” with Kelly, and that they specifically discussed the scheme to send an alternative list of electors to Congress. (Kelly’s advice to Hitt is protected by attorney-client privilege, a spokesman for Kelly told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. He added that Kelly “believes Joe Biden is the duly elected president of the United States.”)

The right is starting to worry about Kelly’s chances. “The Wisconsin G.O.P. has a problem—they’re losers,” a recent National Review column said, calling Kelly “charmless” and fretting that the Party was “fixing to lose their advantage in the judicial branch in April.” Meanwhile, Kelly’s treatment of Dorow may have backfired. After her defeat, she released a perfunctory statement endorsing him and has since gone silent, even deleting her Twitter account.

Despite the recent spate of losses by Wisconsin’s conservatives, they show no signs of moderating. This month, the legislature blocked a requirement, made by the Evers Administration, that seventh graders be vaccinated against meningitis. The state Supreme Court also reappointed Jim Troupis—Trump’s attorney, who tried to have hundreds of thousands of ballots thrown out in the 2020 election—to another three-year term on the state’s Judicial Conduct Advisory Committee. Although recent polling by Marquette University Law School shows that two-thirds of Wisconsin’s registered voters want abortion to be legal in all or most cases, two weeks ago the legislature unveiled an abortion bill that would update the 1849 law by adding exceptions only for rape and incest. Even those concessions were made reluctantly. The bill’s co-author, Donna Rozar, said, “I know there can be positive outcomes in rape situations where babies are carried to term.”

The race between Kelly and Protasiewicz has turned increasingly acrimonious. Last week, during their only debate, Protasiewicz called Kelly a “true threat to our democracy” and said that he would uphold the 1849 abortion ban. “This seems to be a pattern for you, Janet—just telling lies about me,” Kelly responded. “You don’t know what I’m thinking about that abortion ban.” After the debate, they refused to shake hands. (Later that day, Kelly appeared at an event headlined by Matthew Trewhella, an anti-abortion pastor who once endorsed killing abortion providers as “justifiable homicide.”)

For progressives, there is pent-up hope that, after more than a decade, this election may finally free them from minority rule. Jeff Mandell, the co-founder of Law Forward, has all but promised that, if Protasiewicz wins, he and his colleagues will bring a case challenging the state’s electoral maps. “Everything follows from the gerrymandering,” he said. In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that, because gerrymandering involved “political questions,” federal courts could not offer a remedy. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts encouraged those seeking redress to do so at the state level. “Roberts expressly invited people to take these cases back to your states and see if your state constitution provides you a remedy,” Mandell told me. “That’s what happened in Pennsylvania. That’s what happened in North Carolina. People brought these cases, and the state courts protected them.”

For Mary Lynne Donohue, the retired attorney in Sheboygan, any optimism she has for a similar outcome in Wisconsin is tinged with a terrifying sense of fatalism. “People kept saying, ‘We’ll just wait until the next census,’ ” she told me. “I tell them, ‘There’s nothing that’s going to change. This is a permanent majority.’ People need to come to grips with this. I don’t know what natural or unnatural force will ever change that.” She paused. “Except for this upcoming Supreme Court election.” ♦

Source: A High-Stakes Election in the Midwest’s “Democracy Desert” | The New Yorker